There is a myth that skilled writers are born with that talent. Some people may picture a blossoming author sitting in front of a screen, where beautifully crafted sentences and paragraphs emerge fully realized, seemingly gifted to the page. The truth is that writers are made, not born. And one of the most useful skills educators can teach students is how to write fluidly, clearly, and concisely. Still, it is not uncommon for people to remember their first research paper as an assignment essentially being thrown at them, with minimal guidelines or instruction on how to write it.

A critical piece of Windward’s mission is preparing its students for the transition to mainstream schools. Giving them the tools to succeed academically not only eases this transition but also instills confidence in our students as they venture into new educational settings. To support this goal, the School established a capstone program for eighth and ninth graders: Study Skills, a sequential curriculum that systematically instructs students in all the skills needed for preparing a research paper and, later, presenting the project to a group of peers.

Almost without fail, those Windward alumni who stayed at the School through the eighth grade note Study Skills as being particularly impactful on their journeys through high school, college, and, in some cases, their careers. What is enduringly special about this program that alumni point to it, sometimes decades later, as being a formative experience? As it turns out, quite a bit.

THE FOUNDATION

Years before students sit in their first Study Skills class, they are gradually, methodically laying a foundation for understanding the formal writing process. As one of three dedicated language arts periods per day, Windward’s expository writing program teaches students to express themselves in written form through explicit instruction in writing sentences, paragraphs, and compositions. Structured writing time, like all the School’s programs, is designed to provide the most robust supports in the beginning, followed by reinforcement, review, and the gradual release of responsibility to the student.

Starting in the earliest elementary grades, students begin learning how to write at the sentence level. As soon as the first grade, students generate oral paragraphs as a class, while second grade classes progress to writing teacher-guided paragraphs. Third graders continue practicing paragraph writing activities, which progress to two-paragraph essays by fourth grade. Teachers present students with the Advanced Composition Outline planning tool in fifth grade; students then tackle their first five-paragraph composition with an introduction, body, and conclusion. In sixth and seventh grades, the assignments are stretched little by little, and students become accustomed to writing essays with several body paragraphs.

In structuring the content itself, students are in no way left to navigate this process alone. They learn about the concept of the inverted triangle—or a blueprint for organizing the introduction to an essay—that first presents a broad overview of the topic, followed by narrowing statements highlighting the body paragraphs’ focus, and, finally, a thesis statement that outlines the main argument or purpose. The triangle is flipped for the conclusion: first a restatement of the thesis, then statements summarizing the body of the essay, and, lastly, a general statement on the topic.

Providing students with a deeply structured approach to writing gives students the scaffold they need to build their skills. Former Director of Language Arts and current Special Projects Advisor to The Windward Institute Betsy MacDermott-Duffy notes, “We always compare it to a recipe. You can get creative after you’ve got the basics down, but you have to start with the basics.”

See this example introduction for a multi-paragraph essay on Eleanor Roosevelt:

THE FRAMEWORK

Constructing the framework that culminates in the Study Skills program begins in the lower schools, as students begin learning about the elements of print. Coordinator of Study Skills and Westchester Middle School Teacher Tim Caccopola explains, “We prime the students with early work in looking at the basic features of books: identifying the title, the table of contents, and the index. They’ll use the table of contents and the index to locate little subheadings and subsections and then use those keywords to locate more information separate from just the general topic. For example, on the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, we know a subsection was on sweatshops and working conditions. We’ll go to the index and see if we can locate that information.”

Through their language arts, social studies, and library coursework, students build knowledge about reliable research sources, close reading, notetaking, summarizing, and outlining. They begin to hone their presentation skills in the fourth and fifth grades, as they learn about creating a slide deck in PowerPoint for reporting out to the class on a given topic. In middle school, students frequently participate in read-alouds, an exercise that allows them to practice reading with expression, projecting their voices, and pacing appropriately so that their audience remains engaged.

BUILDING BLOCKS

Study skills groupings—like all language arts classes —are homogeneous. Arranging cohorts in this way allows Study Skills teachers to offer supports aligned with student need at each stage of the process. For example, some groups may require more support for a longer period of time, while other groups may more quickly shift to independent work. Associate Director of Language Arts Colleen McGlynn says, “Having the kids grouped with their language arts group makes it much easier to be able to differentiate the level of independence.” At all levels, because students are generating one research paper each quarter, they continue to refine their research, writing, presentation, and time management skills as the year progresses.

Arranging cohorts [homogeneously] allows Study Skills teachers to offer supports aligned with student need at each stage of the process.

THE RESEARCH PLAN

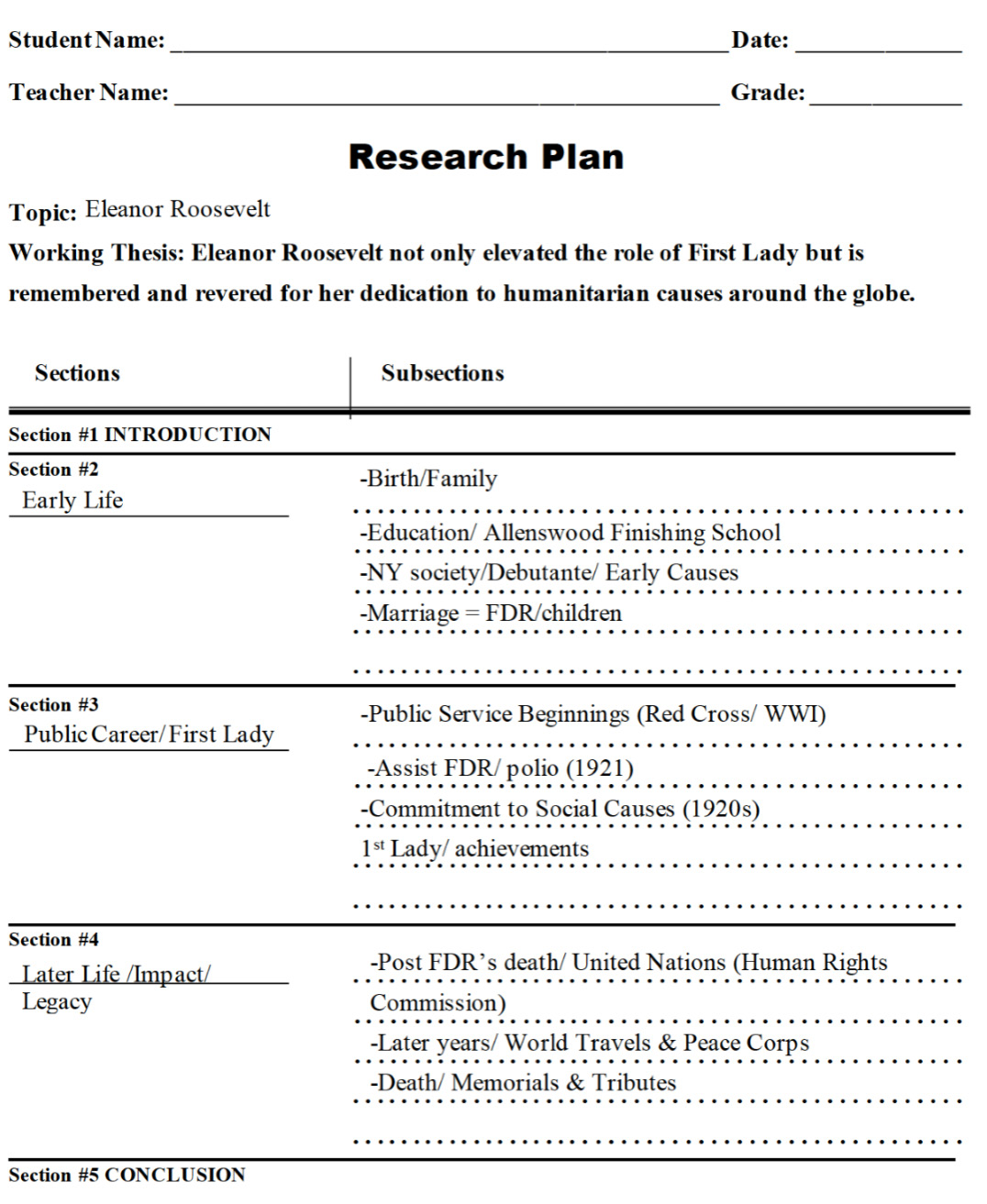

Approaching a multi-page research paper can at first feel overwhelming for many students, especially those with challenges around executive function. In order to break down this larger task into manageable chunks, creating a solid Research Plan becomes invaluable in guiding a writer’s efforts. This document—meant as a quick reference that a student can return to throughout the process—opens with the working thesis, followed by divisions for each section, naming their topics; each section is then divided into subsections, outlining the main ideas to be covered by the body paragraphs. Students can follow this guideline step by step as they progress through the assignment, ensuring that content remains on track.

Though deceptively barebones at first glance, the Research Plan has proven such a useful tool for students that returning alumni often seek out Caccopola to share, “I still make a research plan to map out my projects at the beginning!”

Take a look at this simple, effective example of a Research Plan for an essay on Eleanor Roosevelt:

Note that each section has a title describing its focus, with subsection topics clearly divided into content areas. If a student is tempted to veer off on a tangent at any point, they can refer to the Research Plan as a reminder of the main points supporting their thesis.

THE ADVANCED COMPOSITION OUTLINE

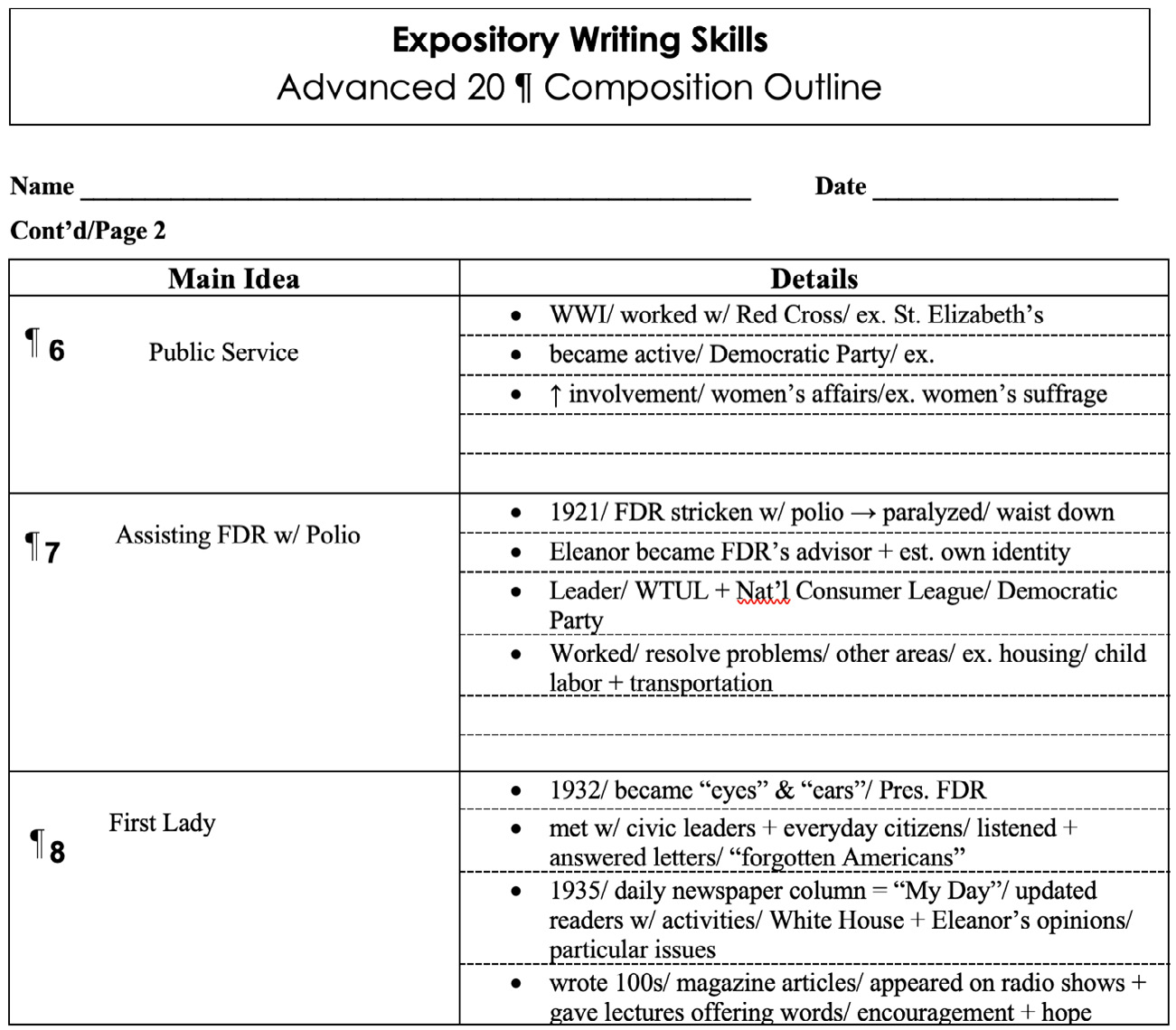

If the Research Plan acts as a framework for approaching the project, the Advanced Composition Outline functions as an instruction manual for building each piece of the essay’s structure. Typically, Windward students are introduced to this planning tool in fifth grade, so they have had years of experience using it to inform their writing processes by the time they begin Study Skills.

Notice how this portion of the outline fleshes out section 3 from the Research Plan previously shown, outlining the details to cover under each subsection of the main section.

As students immerse themselves in the research process, they synthesize information from multiple sources using a system of note cards, which they group together by main section and additionally by subsection. Caccopola notes, “This multisensory element is one strategy that supports students’ executive functioning. Building up their notes and source citations on these tangible cards helps keep all their information organized sequentially and chronologically.” Prior to creating the Advanced Composition Outline, students can easily rearrange note cards into an order that makes sense; then they can capture this information in bullet points on the outline, which maps out the content progression and is students’ guideline as they draft their essays.

DRAFTS, DRAFTS, DRAFTS

One differentiator of the Study Skills program is the ongoing feedback students receive throughout the writing process. In many schools, students are assigned a research paper, complete it independently, and submit it in its entirety for grading. The problem with this approach is that if a student is consistently making similar grammatical errors or using awkward syntax, for example, these errors will reappear throughout the paper. Making corrections as they write not only eliminates repetitive mistakes, but it also gives students real-time context, aiding in retention of the information.

Consistent feedback from teachers is also critical due to the technical nature of formal writing, as regular input on their progress helps build students’ confidence in this area. “For example, we’ll collect just the introduction and give feedback on that. We’ll collect just section one and give feedback on that. Then we’ll look at section one and two and give feedback. There are multiple steps to drafting,” Caccopola notes.

MacDermott-Duffy shares, “As another example, a Windward student isn’t creating a thesis—the statement that drives the whole paper—without input from the teacher. If the statement is too narrow, it won’t support an entire five- or six-page research paper; if the statement is too broad, it is equally difficult to support. Getting that teacher feedback at every stage of the process is so important.”

THE PRESENTATION

To cap off the project, students create a PowerPoint presentation distilling the multitude of information in the research paper into a briefer, visual format, which each student then delivers to their class. Typically introduced during the second semester of Study Skills, after students have already tackled one to two research papers, the PowerPoint aspect of the project is noted as a highlight of the program by teachers and Windward families. Caccopola shares, “Parents and guardians really appreciate the instruction and the modeling on PowerPoint presentations, having students be able to present on their topics for 8 to 10 minutes and then be assessed on the visual aspects, the aesthetics, the content, and the delivery of their presentation.”

Developing strong expressive language is a powerful tool students can take with them to their next schools or even, eventually, to their careers. “Getting in front of their peers and presenting on topics, informing their audience: There are so many layers. There are so many life skills there,” Caccopola continues. Effective oral communication is particularly important for higher education and the workforce, so honing and enhancing those skills proves incredibly valuable in the long term.

“Students become aware of their writing and what good writers do. It’s not just about the content of what they’re writing. They’re also thinking about how they’re writing it.” — Colleen McGlynn

IMPACT OF THE PROGRAM

It’s impossible to overstate the profound impact that the Study Skills program has had on Windward students. It is not just that students learn how to craft a piece of formal writing, though that is an important skill, which will serve them well; it is that they begin to understand how to approach the process as a whole. MacDermott-Duffy notes, “While refining the program years ago, what emerged was the importance of drafting a Research Plan. If the end product is not successful, that shows there is something wrong with the plan. So, we ensure from the beginning that elements ranging from topic, purpose, and audience to outlining the draft to narrowing the thesis statement are all pointed toward the quality of the final product.”

And not only are students being explicitly taught—over a span of years—how to research a topic, utilize source materials, and write coherently and independently, but they are also gaining insights into what differentiates good compositions from weaker pieces. Through the systematic exploration of the writing process, McGlynn explains, “Students become aware of their writing and what good writers do. It’s not just about the content of what they’re writing. They’re also thinking about how they’re writing it.”

When students have received cumulative instruction in effective writing, from lower school onward, tackling a momentous project like a research paper feels less daunting. They have already accumulated the skills they will call upon to complete the project; it then becomes a matter of flexing those skills with the support and guidance of a dedicated teacher.

Students gain crucial experience in time management, as well, as they use their Research Plan to divide the larger project into smaller tasks, setting deadlines for themselves along the way. “They have a calendar where they keep track of when each step is due, and I think that’s really helpful. That’s absolutely a skill that the kids could take with them for life,” adds McGlynn. Indeed, many alumni have echoed that sentiment. One alumna profiled recently in The Compass, who now works at the federal level drafting public policy, shares, “The Study Skills program truly built the foundation for how I [approach writing], even today.”

For many Windward students who struggle with executive functioning, completing a massive assignment like a multi-page research paper can be incredibly taxing on the brain, even with an organizational framework laid out for them. This is due to the limited capacity of working memory, which is a part of the brain’s executive function that temporarily holds and manipulates information. Accumulating knowledge about a subject over time and in multiple contexts eases that burden. Students gradually build background knowledge as they encounter material, making connections across subject areas. For example, students may be assigned to write about Andrew Carnegie in Study Skills; at the same time, they are learning about the gilded age and the robber barons in their social studies classes. McGlynn explains, “So they’re able to use their knowledge from social studies to help them access some of this material in Study Skills, and then Study Skills is really building this wealth of knowledge. They’re reading at least four, maybe five articles about Carnegie, or about the historical time period, to deepen that understanding before even getting to write the paper.”

Knowledge building has emerged in recent research as an important piece of reading comprehension.

Knowledge building, or cultivating deep knowledge in students through curriculum that supports that concept, has emerged in recent research as an important piece of reading comprehension. Windward has embraced this approach for years, and the Study Skills program is a clear reflection of that. Associate Head of School for Academic Programs Lisa Murray notes, “Because the research is so solid on knowledge building aiding reading comprehension, we’re constantly looking for ways to build knowledge even more for our kids while they’re at Windward. And I think Study Skills really speaks to that because it’s a whole yearlong exercise. Each of the projects is building that deeper knowledge, connecting to other content areas, mainly history, but other areas as well, like science. It makes our academic program such a standout.”

LOOKING TOWARD THE FUTURE

As the program has evolved, its coordinators have worked toward making it more inclusive, from adding more projects focused on different cultures to including more uses of assistive technology. “For those kids that struggle with handwriting and legibility, the note card process can be prohibitively labor intensive. We’ve started to adopt more assistive technology, with digital note cards and editable documents that students can work through online,” shares Caccopola.

In collaboration with Director of Educational Technology Joan McGettigan, Study Skills coordinators and teachers also use various tools within Microsoft Teams to help students form effective queries, evaluate their sources, and obtain real-time feedback on presentation skills. Adds Caccopola, “Teams, which we use more widely as a program to help students with time management and tracking assignments, also offers Learning Accelerators: Search Coach—a simple app that assists students in forming effective queries and identifying reliable resources— and Presenter Coach.” Presenter Coach allows students to record their presentations and receive instant feedback on voice intonation, tone inflection, modulation, gesturing, and use of filler words. The program then shares percentages for areas that need improvement.

As the culmination of years of foundational work in reading comprehension, notetaking, outlining, and writing, Study Skills offers Windward students a unique toolkit that is both unmatched and incredibly useful—wherever their journeys take them. This toolkit’s purpose is not limited to its practical application, as it also empowers students to approach future writing assignments with confidence, secure in the knowledge that they are prepared. Alumni often note that they turn to elements of the program—such as how to effectively manage their time, how to balance and track deadlines, and how to drive a project using a research plan—to inform any number of tasks related to their academic journeys and, later, their careers. It is rare that a single course has such a lasting effect. And while all Windward programs are guided by the commitment to empower students to achieve unlimited success, few are more illustrative of this disciplined approach than Study Skills. At any alumni event, simply ask an alum, “Which Windward program had the biggest impact on you?” Nine times out of ten, they will answer, “Study Skills.”