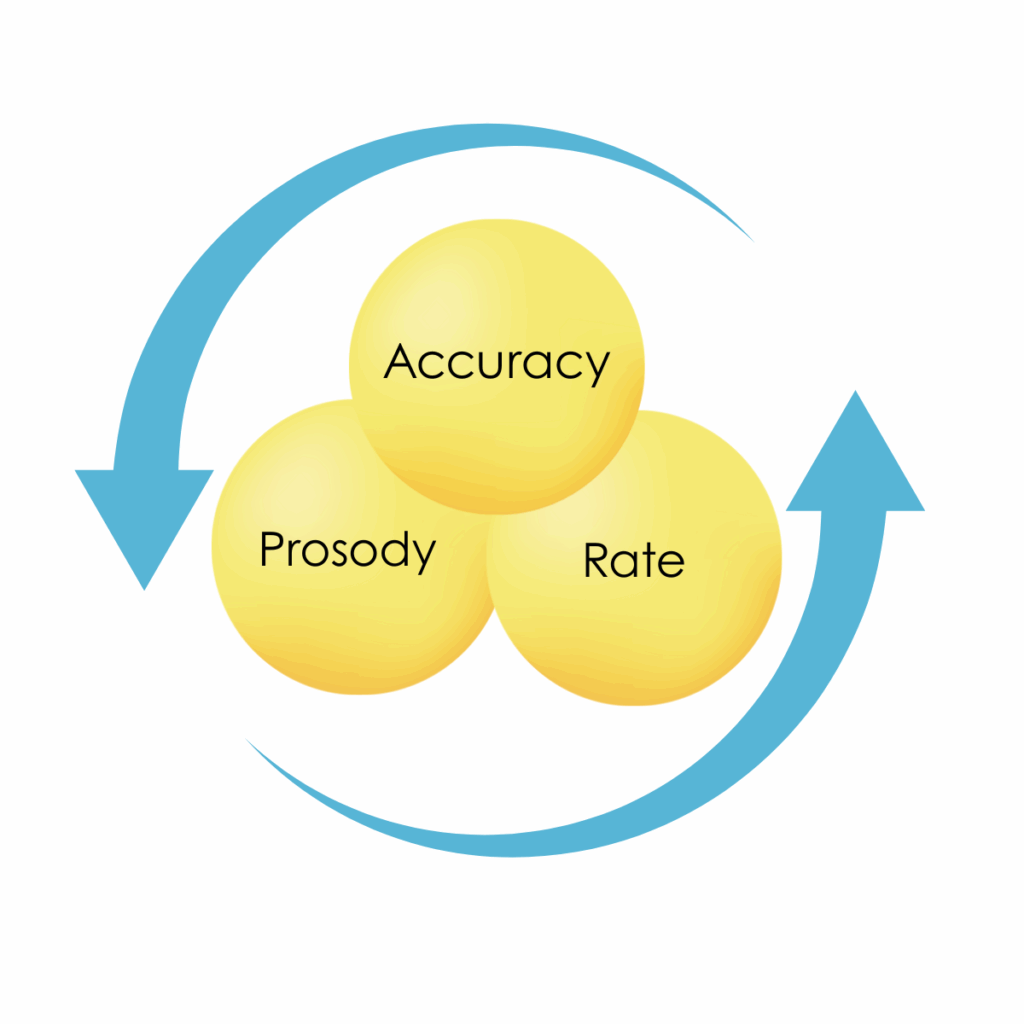

Educators rely on a variety of literacy assessments and data points to understand and support student growth. One widely used measure is Oral Reading Fluency (ORF), which provides valuable data about a student’s fluency when reading aloud. Fluency is described as the rate, accuracy, and prosody of reading. Research has shown a strong relationship between oral reading fluency and reading comprehension (Fuchs et al., 2001; Hasbrouck & Tindal, 2006, 2017), and fluency is one of the five major components of skilled reading identified by The National Reading Panel (2000).

Fluency Measures

ORF measures serve multiple roles in literacy instruction:

- Diagnostic insight: ORF can help screen for potential reading challenges by identifying students who may struggle with fluency and comprehension.

- Developmental monitoring: By comparing student performance to national norms, educators can understand how students are progressing relative to their peers.

- Progress monitoring: ORF provides data over time, helping educators track student growth.

- Instructional planning: Results from ORF assessments can inform targeted interventions and guide instructional decisions.

Words Correct Per Minute

During an ORF assessment, students read a grade-level passage aloud for one minute. The passage should be unfamiliar to ensure an accurate measure of decoding and fluency. Teachers record errors, including missing words, incorrect words, and switching the word order, in addition to self-corrections. Teachers then calculate Words Correct Per Minute (WCPM) by subtracting errors from the total words read (Fuchs & Fuchs, 2003).

These scores can then be compared to national fluency norms, which have evolved over time to reflect diverse student populations. Hasbrouck and Tindal’s norms, updated in 2017, are a popular and reliable resource for educators. They are based on large samples of students across different states and school districts. These norms provide a comparison measure in relation to the larger population.

What About Prosody?

To be considered a skilled reader, students need to read accurately, smoothly, and with rhythm. While ORF assessments typically focus on rate and accuracy, they do not directly measure prosody, which includes the rhythm, tone, and expression that contribute to meaning making and deeper comprehension. Several researchers have created rubrics as an assessment measure to view the elements of prosody: expression and volume, phrasing, smoothness, and pace (Rasinski, 1991).

With advancements in technology, digital tools that include prosody are available commercially, and advancements are continuing to be made. These digital tools track students WCPM, accuracy, and provide the ability to record in order to consider prosody elements like phrasing and tone. Many also include comprehension measures like student retells with the grade level normed passages. This additional data can provide useful information to teachers for both benchmark assessments and progress monitoring.

Benchmarking and Progress Monitoring

When used for benchmarking, ORF assessments are typically administered three times per year to all students. The data points they yield help identify students who may need additional support and provide a foundation for instructional planning and family communication.

For students who fall significantly below benchmark, ORF measures are key indicators for ongoing progress monitoring. These students should be assessed more frequently, often once or twice a month, to track growth and guide intervention. Additionally, graphing WCPM over time can reveal trends, highlight areas of concern, and support instructional adjustments to meet individual literacy goals.

Implementation Considerations

- Purposeful implementation: Schools should reflect on the purpose, frequency, and structure of ORF assessments and tasks to ensure they support broader literacy goals.

- Time and scheduling: Administering ORF assessments consistently requires careful planning and scheduling to reduce impact on instructional time.

- Scoring consistency: Training is essential to ensure fair and accurate scoring across classrooms.

- Fluency vs. speed: ORF tasks should not feel like speed drills. Thoughtful implementation includes careful task framing, discreet use of timers, and teacher feedback that addresses all aspects of fluency.

- Comprehension checks: Comprehension can suffer when students are focused on speed, not meaning. To build strong reading habits, it is important to hold students accountable for reading ORF passages at a rate that supports understanding. This can be done verbally with passage retells or by responding to comprehension questions.

What’s in a Minute?

Fluency is a key component of skilled reading, and ORF assessments provide a quick yet powerful way to gather valuable data on this critical area of development. Used consistently, these one-minute probes enable teachers to track growth over time, identify students who may need additional support, and celebrate meaningful progress. When paired with other measures, ORF becomes an integral part of a comprehensive progress monitoring system—offering deeper insights into student learning and helping educators target instruction and interventions that support all students on the path to skilled reading.

References

Fuchs, L.S., Fuchs, D., Hosp, M.K., & Jenkins, J.R. (2001). Oral reading fluency as an indicator of reading

competence: A theoretical, empirical, and historical analysis, Scientific Studies of Reading, 5(3), 239- 256.

http://doi.org/10.1207/S1532799XSSR0503_3.

Fuchs, L.S., & Fuchs, D. (2003). What is scientifically-based research on progress monitoring?, National Center on

Student Progress Monitoring: Washington DC.

Hasbrouck, J., & Tindal, G. (2006). Oral reading fluency norms: A valuable assessment tool for reading teachers,

The Reading Teacher, 59(7), 636-644, doi: 10.1598/RT.59.7.3.

Hasbrouck, J., & Tindal, G. (2017). An update to compiled ORF norms (Technical Report No. 1702). Eugene, OR,

Behavioral Research and Teaching, University of Oregon.

National Reading Panel (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific

research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the subgroups.

Bethesda, MD: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, National Institutes of Health.

Rasinski, T. (2004). Creating fluent readers: A growing body of evidence points to reading fluency as an

important factor in student reading success, Educational Leadership, 46-51.