By Jamie Williamson, EdS, Head of The Windward School and Executive Director of The Windward Institute

Think about the last time you went to the doctor for a checkup.

Depending on your age and family history, they may have taken blood to run a lipid panel and check levels of total cholesterol, HDL and LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides. If you were shown to be at risk for heart disease, they may have followed up to discuss lifestyle changes to reduce risk. They may have even provided further information about symptoms of a heart attack or stroke and what to do if you experience any symptoms. That information also may have been displayed prominently in the doctor’s office, for example, a poster with the acronym BE FAST outlining the signs of a stroke and when to seek emergency care. The above experience has become fairly common, but it was not always that way.

In the 1920s, having cardiovascular disease (CVD) was considered a death sentence. With the creation of

the American Heart Association in 1924 and the decades of research that followed, researchers and doctors gained invaluable insights into the causes of heart disease and what can be done to mitigate risks. What resulted was one of the great public health achievements of the last century, a major decline in deaths related to heart disease. In fact, since the 1960s, the mortality rate from CVD has declined more than 70%, which is attributed to significant improvements in screening, prevention, and treatment of CVD and related risk factors (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018). Many of the measures patients now consider routine

are, in large part, the result of years of data that has coalesced into a robust framework consisting of greater public awareness, regular screenings, and early interventions (Ford & Capewell, 2011). Now imagine if we had the same infrastructure in place for the identification and remediation of dyslexia and other language-based learning disabilities.

CONSTELLATION OF FACTORS

Dyslexia is a complex disability that is neurobiological in origin, with neither a single causal factor nor the same presentation in every individual. Advances in neuroscience have made it possible to capture imagery of structural and functional differences in the brains of individuals with dyslexia, which, in some cases, have been detected as early as infancy (Gaab & Duggan, 2024). Brain scans cannot diagnose dyslexia, nor is that what this research aims to do. However, studies showing marked differences in the brains of those with dyslexia help inform the neurological basis of the disability and point to the fact that some students enter kindergarten with a neurophysiological disadvantage for learning to read.

Some students enter kindergarten with a neurophysiological disadvantage for learning to read.

Up to 50% of people with dyslexia also have developmental language disorder

(DLD), a brain-based disability that impacts a person’s ability to learn, organize, and understand oral language

(Adlof & Hogan, 2018). Persistent challenges related to DLD include vocabulary and new word learning,

comprehension, and understanding and expressing ideas verbally.

Both dyslexia and DLD are highly heritable, with the former occurring in roughly 45% of individuals who have a

first-degree relative with the disability (Snowling & Melby-Lervåg, 2016).

So, we know that there are differences in the brains of individuals with dyslexia— detectable as early as infancy—and we know there is a high comorbidity rate with developmental language disorder, as well as evidence showing a large percentage of people with dyslexia who have a parent or sibling with the condition. Reading researchers have also come to consensus that multifactorial identification models, looking at risk factors, promotive factors, and protective factors, are most likely to provide the clearest picture of who may be at risk for reading problems. “Risk factors are variables that increase the likelihood of severe and persistent difficulties learning to read” (Catts & Petscher, 2022, p. 174). In their cumulative risk and resilience model of dyslexia, Catts and Petscher outlined these risk factors:

- Phonological deficits: difficultieswith recognizing, manipulating, recalling, and reflecting upon the sounds of spoken language

- Language impairments: deficits in vocabulary, grammar, and overall oral language abilities

- Attentional deficits: 25%-40 overlap with dyslexia, higher than would occur by chance (Willcutt Pennington, 2000)

- Visual problems: deficits in visual temporal processing and visual attention; problems with visual crowding

- Trauma/stress: neurological effects of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) when co-occurring with other risk factors

Promotive factors are those that are good for all readers, not only for those at risk: for example, a rich language

environment and evidence-based core reading instruction. Protective factors, or resilience factors, are moderators in that they may offset risk:

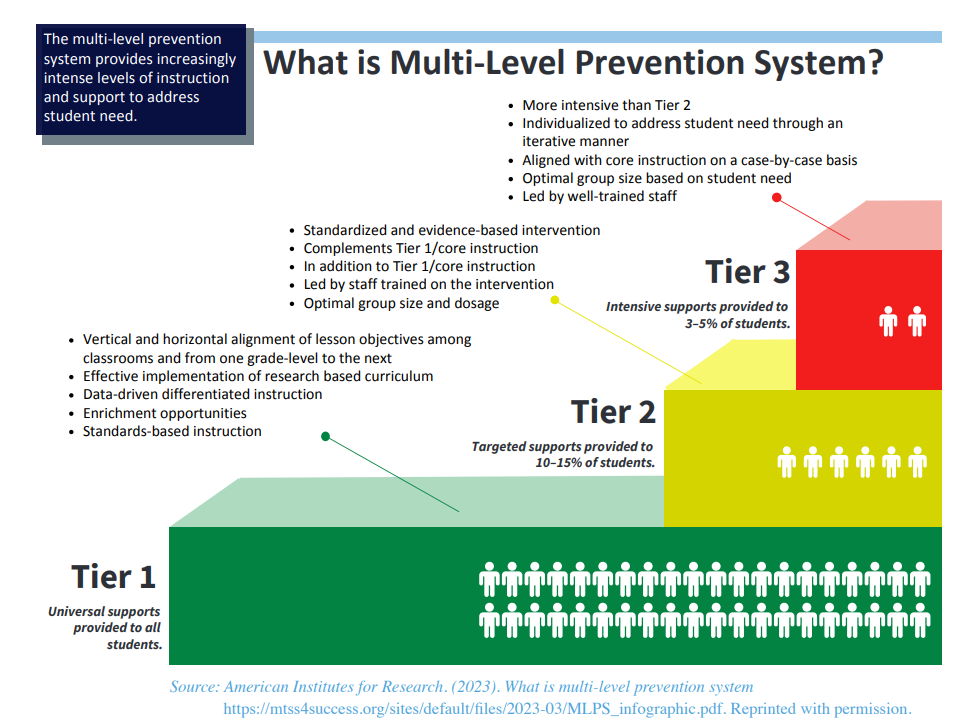

- Instruction: systematic, structured, intensive in tiers 1, 2, and 3

- Growth mindset: internalizing the idea that one can grow their intelligence, an effect that maybe stronger for children at risk (Petscher, 2017)

- Task-focused behavior: high engagement (effort) in tasks and persistence through challenges

- Adaptive coping strategies: belief that one’s effort drives progress, anchored with goal setting and positive outlook

- Teacher, family, and peer support: teacher encouragement, peer acceptance, nurturing family relationships, rich at-home literacy environment

- (Catts & Petscher, 2022)

All the data outlined above, amassed over decades of research, illuminates factors that increase the likelihood that a child will be at risk for reading difficulties. It is notable that based upon the above considerations, level of risk can be assessed prior to the onset of formal reading instruction. This is a critical distinction, because studies have also shown that when students receive interventions as early as kindergarten or first grade, they are more effective. (Wanzek & Vaughn, 2007)

It is notable that level of risk can be assessed prior to the onset of formal reading instruction.

IT MAY BE TIME TO RETHINK SCREENING

One of the enduring consequences of the “wait to fail” approach to reading intervention is the devastating impact it can have on students’ well-being and long-term academic success.

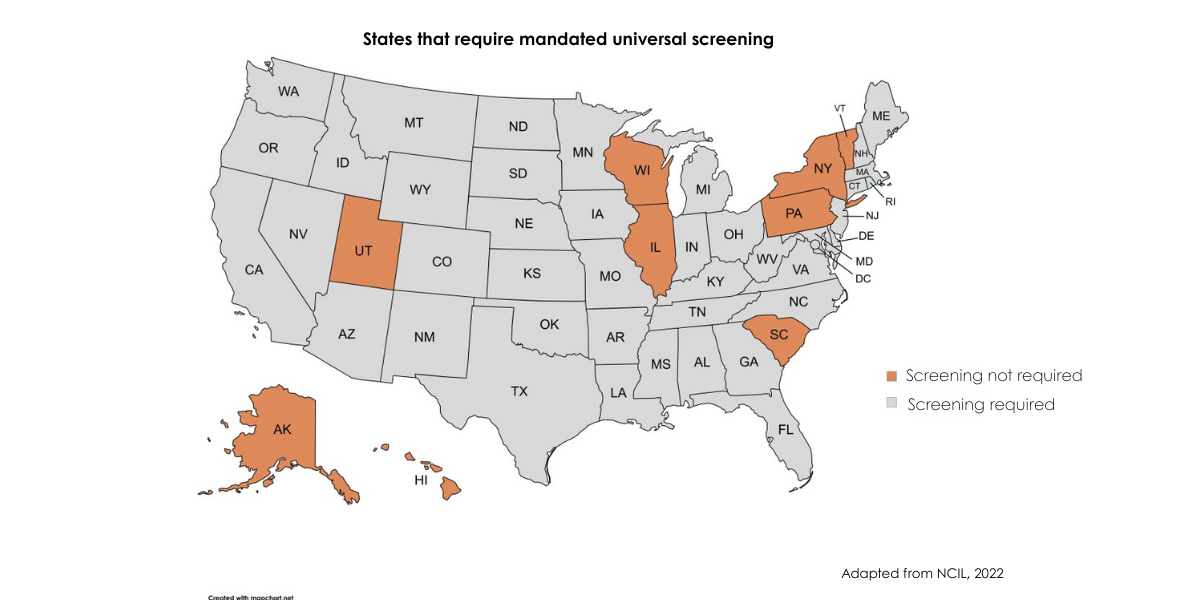

As public awareness of reading disabilities has grown in recent years, lawmakers have responded in increasing numbers by introducing legislation aimed at addressing the literacy problem in the U.S. To date, 40 states and the District of Columbia have passed laws mandating screenings, for example.

And while this is an encouraging sign, there is still much work to be done to solve the conundrum of early identification, including commonsense steps that can be taken to screen young children early, often, and in multiple contexts.

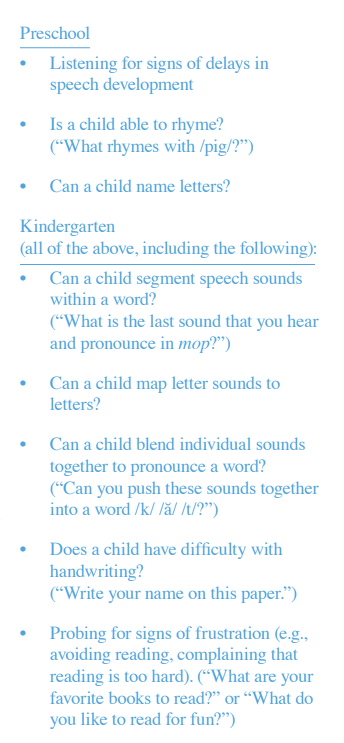

Identifying children at risk for reading problems can begin as early as age 3 (Puolakanaho et al., 2007), by gathering data on early language skills from developmental screeners, family histories, and pre-K screeners. Many children with dyslexia also have some degree of difficulty with spoken language, which, when combined with additional factors, can increase the probability of encountering issues with learning to read (Snowling et al., 2016).

Developmental screeners, conducted by pediatricians or other care providers, typically assess five domains of functioning: 1) cognitive, for example, counting and identifying shapes; 2) language, or speech and comprehension; 3) fine motor, such as writing and drawing; 4) gross motor, as in crawling, jumping, and running; and 5) social emotional, including playing with other children. One early indicator of potentially being at risk for later reading problems, for example, is whether the child was late to begin talking (Lyytinen et al., 2005; Preston et al., 2010; Rescorla, 2002).

Pediatricians can and should also consider incorporating simple literacy screeners into well-child visits, because health providers can be key in referring families to appropriate external reading experts for gathering additional data.

The aforementioned domains of functioning and a complete family history, combined with early literacy predictors, can develop a fuller picture of a child’s likelihood of developing reading problems. Critically, and previously noted, these predictors can be assessed before the child begins formal reading instruction.

There is ample current research in early screening of reading risk that has consistently shown that early, developmentally appropriate measures of phonological awareness, rapid naming, oral listening comprehension, verbal working memory and letter knowledge have solid predictive validity for future

reading success or failure. (Colorado Department of Education, 2024)

While evidence mounts confirming the urgency of early intervention for reading problems, some experts have answered the data by designing simple, literacy specific screeners for preschoolers. One promising screener, the EarlyBird Program, was developed by Dr. Nadine Gaab, Dr. Yaacov Petscher, and Carla Small in partnership with Boston Children’s Hospital and the Florida Center for Reading Research. This gamified, engaging assessment includes the foundational components of early reading in order to identify at-risk pre-K and kindergarten students, and it can be deployed in school or home settings.

A familiar refrain for many educators who align with structured literacy principles is “screen early, screen often.” So, how does this translate on an actionable basis? It means screening children before they enter school for

developmental milestones that affect risk. And it means screening students in grades K and 1 at least two to three times per year and examining that data for signs that a student may require targeted interventions. This approach necessitates a solid core reading program, which benefits all emerging readers but will specifically reduce the number of false positives that can occur when screening kindergartners. The floor effect—when

a massive number of students score positive for being at risk for reading problems—is most pronounced early in

the school year for the youngest students, as many students enter school with vastly different literacy experiences prior to beginning kindergarten (Catts, 2021).

To differentiate those students who will go on to be typically developing readers from those who require interventions, educators can screen students in October of kindergarten after some reading instruction has begun, screen again in the winter, and, finally, screen again in the spring. Screening after reading instruction has begun and testing again before the end of school year can help narrow down those students who

may be at risk for reading problems and require interventions. But of course, once educators have this data,

there needs to be the infrastructure in place to act upon it, which can present logistical and financial barriers

for many schools and districts.

EARLY IDENTIFICATION’S PURPOSE IS EARLY INTERVENTION

We know that the earlier we intervene, the better children do. Based on a meta analysis by Wanzek et al. published in 2018, studies show that word reading interventions are most efficacious for improving literacy outcomes when employed in kindergarten and first grade, as opposed to later grades. Partly this is due to the incredible neuroplasticity of children’s brains from birth to age 7 (Scorrano, 2021). Also worth noting is the fact that as students advance through elementary school, they transition from learning to read to reading to learn

(Chall, 1983). Disparities in reading skills then become more pronounced, with greater negative effects on academic performance and self-confidence. Studies show that 79% of struggling readers who fall behind by third grade never catch up with their peers (National Center for Education Statistics, 2019), which has a ripple effect that is far reaching: Students who are not proficient readers by fourth grade are four times more likely to drop out of high school (Annie E. Casey Foundation, 2011).

This is why a solid framework for core reading instruction and intervention becomes critical, as the investment by educators—both in time and funds— in early interventions not only keeps students engaged in learning but helps alleviate pressures on the system later.

In practical terms, what this approach can look like is pairing screening tools with short-term interventions to more accurately assess dyslexia risk (Miciak & Fletcher, 2020). If schools or districts have a solid response to

intervention (RTI) model in place, with robust progress monitoring and well-established tiers of instruction, those

students misidentified as being at risk respond to initial interventions, while those requiring more intensive supports emerge more clearly.

The effectiveness of a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) largely hinges upon students receiving instruction that is closely aligned with their needs (Al Otaiba et al., 2009). “For some children who fail screening (and follow-up assessments), the most appropriate action is to provide Tier 2 supplemental code-based instruction

that involves more explicit instruction, scaffolding, and practice” (Catts & Hogan, 2020, p. 10). However, for some students—those at highest risk based on records related to developmental milestones, family history, and initial screenings—moving directly into tier 3 instruction may provide greater benefits than moving them into tier 2, waiting for additional data, and then moving them to tier 3. Compton et al. (2012), for example, found that close examination of initial screenings can be predictive as to which students are unlikely to respond to tier

2 interventions; in these cases, students would be best served by immediately receiving intensive, tier 3 interventions.

In all cases, having an established, evidence-based system of support that relies upon progress monitoring

to identify and address learning gaps as they occur leads to better literacy outcomes, both for typically developing readers and students who struggle.

In an effort to shine a light on the importance of moving away from a reactive approach to reading intervention, Ozernov-Palchik and Gaab (2016) coined the term “dyslexia paradox,” which describes the challenges inherent to dyslexia typically being diagnosed after the window for most effective intervention has closed. And while it is never too late to intervene and remediate issues related to dyslexia, the science clearly shows us that the earlier, the better.

WHY EARLY IDENTIFICATION MATTERS

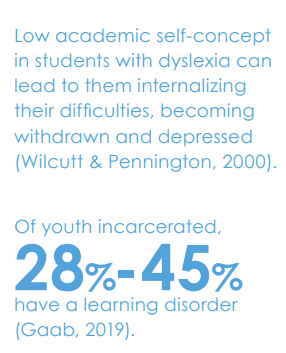

When the system waits for children to essentially fail academically before addressing reading problems, the

ramifications can be extreme and lifelong. A student who struggles to learn to read in early grades, for example, may be driven toward engaging in avoidant behaviors around school. Dr. Vincent Alfonso, in a recent episode of The LDA Podcast, noted that “if we don’t intervene early and students are continuing to be promoted socially or otherwise, but they’re not doing well, there’s a greater probability that they’re going to be turned off to school… and then that makes it more and more difficult to help” (Clouser, 2022).

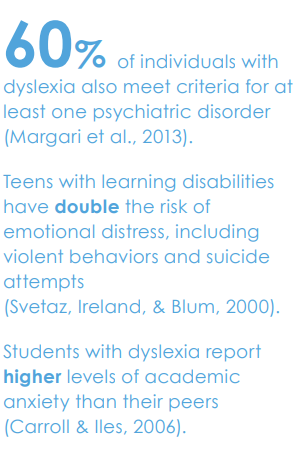

More concerning is that students with dyslexia who consistently struggle academically often suffer loss of self-esteem in general and have higher rates of anxiety and depression than students without learning challenges (Arnold et al., 2005; Chapman et al., 2000). There are a host of other factors related to mental health and social-emotional growth that impact quality of life for children with dyslexia who go undiagnosed.

Conversely, when students with dyslexia receive the intervention they need, in a nurturing and supportive environment, it has a protective effect on mental health. We have seen this anecdotally at The Windward School over many years, but the research bears it out, as well. In one 2023 review of 98 studies worldwide

related to mental health and dyslexia, two sets of researchers cited evidence that suggested “that school connectedness may be a particularly salient protective factor for the socio-emotional well-being

of children with learning difficulties” (Wilmot et al., 2023, p. 12). In fact, children with dyslexia reported much

lower levels of anxiety when they felt that their educators understood and supported their learning disability

(Chiappedi & Baschenis, 2016).

Windward has long recognized the need to provide structured, robust social-emotional learning supports to its

students, as a key piece of remediation is mitigating the negative impact of, in some cases, traumatic experiences students endured prior to joining the School. Many students with dyslexia may also struggle to interpret others’ emotions through facial cues and vocal tone (Operto et al., 2020), or have difficulty recognizing and regulating their own emotions (Rieffe et al., 2008), which underscores the importance of

offering these students both a dedicated social-emotional learning curriculum and an established program schoolwide that helps community members grow their emotional intelligence. For example, the RULER approach—developed by the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence— is an evidence-based program placing a strong emphasis on developing emotional intelligence and social skills among students. (The Windward School is currently in year one of its two-year RULER implementation timeline, with the program slated to roll out to students and families in the 2025-2026 school year.)

Attending to the social-emotional needs and mental health of students with reading difficulties has shown

to positively impact their academic achievement: One recent study by Vaughn et al. (2022) found that when students’ reading lessons were paired with anxiety management interventions, their reading comprehension scores improved.

And although it is heartening to see educators and researchers expanding treatment domains to include the effects of dyslexia on students’ emotional landscapes, and what can be done to ameliorate those effects, it is a reactive approach that treats the symptoms, not the cause. We can do better by our nation’s students with dyslexia.

Just as health outcomes vastly improve when those at risk for heart disease are screened early, assessed for family history, and offered prophylactic measures such as medications and lifestyle changes, taking a preventative approach to dyslexia identification and intervention leads to better outcomes for these students and their families. With proper interventions, 96% of students with dyslexia can reach grade-level

reading expectations (Torgeson, 2009), which is critical to academic and life success. If early identification and early intervention were the norm, I believe that number could climb even higher. We owe it to these kids to catch them before they fall.