One of the most effective ways to deepen student understanding is to have students write about what they are learning. Research consistently shows that writing across disciplines, whether in social studies, science, art, or language arts, reinforces concepts, enhances retention and comprehension, and improves writing quality (Bangert-Drowns et al., 2004; Graham & Perin, 2007; Graham et al., 2024).

Selecting Resources

While textbooks provide foundational knowledge in many subjects, teachers can enrich learning opportunities by incorporating sets of related sources. Books, engaging read alouds, newspapers, reliable online resources, primary sources, and current event articles offer authentic contexts for student reading and writing, providing motivation and background information necessary for knowledge building. Students love exploring contemporary issues in the news and primary source materials, and it not only strengthens their content knowledge but also connects their learning to the real world.

When selecting reading materials to serve as springboards for writing, it is essential to keep in mind the importance of engaging students with increasingly complex texts. This gradual increase in text complexity ensures that students are prepared to analyze, synthesize, and write about challenging ideas (Shanahan, 2025).

Making the Most of Graphic Organizers

Teaching students to write effectively requires sentence-level instruction along with the foundational skills necessary for composition—planning, outlining, drafting, revising, editing, and finalizing— and must be taught explicitly and systematically. Decades of research confirm that explicit instruction, paired with teacher modeling, is one of the most effective approaches to developing writing proficiency (Graham & Perin, 2007; Graham et al., 2024).

To scaffold comprehension and prepare students for writing, teachers can integrate graphic organizers (GOs) during reading and as a framework to organize conceptual information related to a lesson or unit of study. These tools act as visual summaries, helping students identify text structure, key ideas, and the ways in which concepts connect and interrelate (Shanahan, 2005). Once constructed, GOs can serve as a bridge to more linear outlines, providing a clear structure for paragraphs and compositions. Even short written responses can benefit from the structure that these organizers provide.

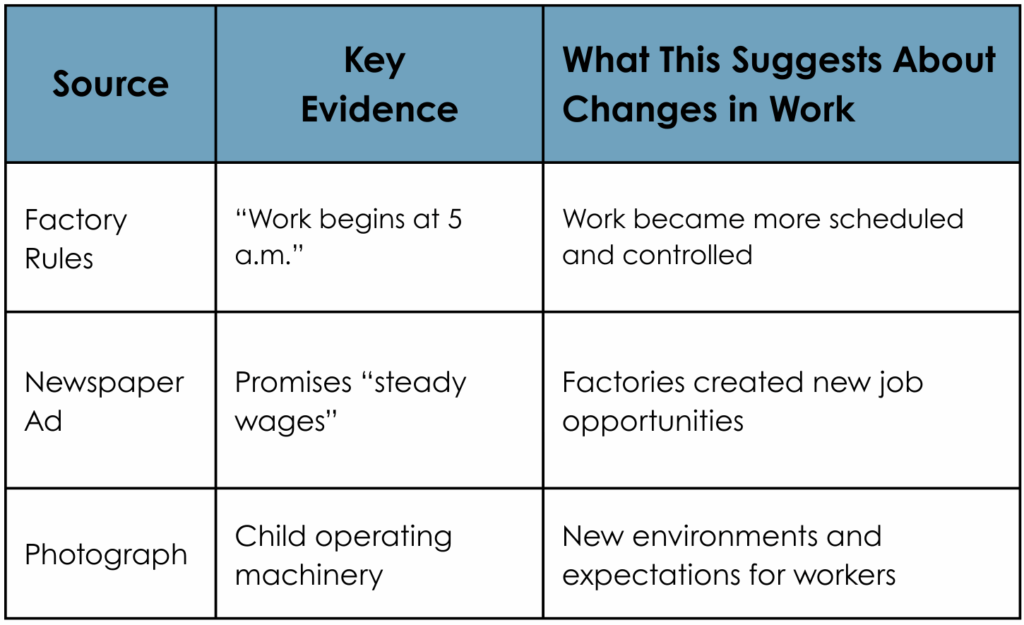

Classroom Example: Using a GO with Primary Sources

For instance, in a middle school study of the Industrial Revolution, students might examine three primary sources—a set of factory rules, a newspaper advertisement for mill workers, and an archival photograph of factory employees—for a writing assignment on factory-based work. A simple GO can help students capture essential ideas.

This organizer is not the final product and not the place for full analysis. Its purpose is to give students a manageable structure for noticing patterns across sources: in this example, the shift toward new work expectations, opportunities, and challenges.

Once completed, the GO becomes a resource for outlining, helping students decide

- what claim they can make about how work was impacted during the Industrial Revolution;

- which pieces of evidence best support their claim; and

- how to organize their ideas into a coherent paragraph or composition.

In this way, the GO serves as a thinking scaffold, supporting comprehension and easing the transition into planning and writing. It is a small but powerful step in a larger, explicit writing process.

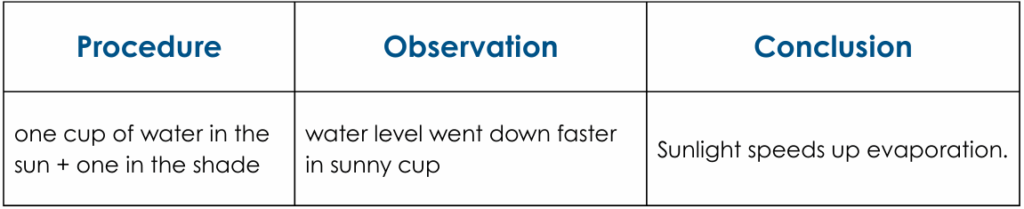

Classroom Example: Using a GO to Support a Short Response Assignment

In science, short written responses often ask students to explain what happened in a demonstration or investigation and what it shows about a scientific idea. A simple three-column graphic organizer can help students briefly organize their thinking before they write.

For example, after an investigation comparing how quickly water evaporates in sunlight and in shade, students might fill in a three-column organizer:

The purpose of this organizer is not to analyze the experiment in detail, but to capture the essential points students will use in their writing: what they did, what they saw, and what it means. Once these ideas are in place, students can move into a short, written explanation that weaves the three pieces together. A prompt might ask students, “Explain what happened in the investigation and what it shows about evaporation.” With their thinking already structured in the organizer, students can focus on producing a clear, accurate, well-written response rather than trying to recall details or decide which ones to include.

Writing-to-Learn Strategies

Developing strong writers is not an isolated goal; it is deeply connected to how students learn across all disciplines. When teachers provide authentic sources, scaffold comprehension with tools like graphic organizers, and directly teach the steps of the writing process, they create opportunities for students to think critically, synthesize ideas, and communicate effectively.

Explicit instruction in specific strategies—such as annotating, summarizing, and outlining—enhances comprehension and retention and supports accurate and cohesive writing across disciplines (Bangert-Drowns et al., 2004). For example,

- quick-write assignments benefit from intentional annotations and margin notes to highlight and order key information;

- repeated practice writing both summary sentences and longer summaries helps students clarify main ideas and communicate information clearly and concisely; and

- paragraphs and essays written from well-developed outlines are less likely to include tangential information and more likely to demonstrate sufficient factual support.

Teacher Modeling

The steps and strategies for written assignments, whether they are short claim-evidence-reason (CER) responses or long compositions, should be introduced through think-aloud modeling, where teachers demonstrate each component of the process while students actively follow along. Repeated teacher demonstrations are essential before expecting students to internalize strategies and apply them independently (Graham & Harris, 2018). Writing is a complex cognitive task, and scaffolding through modeling ensures that students gradually build confidence and competence.

Writing to learn is more than an instructional strategy; it is a pathway to deeper understanding. By embedding these practices into daily instruction, educators help students to become confident writers and informed thinkers. Writing isn’t just about producing essays. It’s about helping students think deeply, connect ideas, and build conceptual understanding that transfers. With the right scaffolds—graphic organizers, outlines, and teacher modeling—writing can become a powerful tool for learning across all disciplines.

References

Bangert-Drowns, R. L., Hurley, M. M., & Wilkinson, B. (2004). The effects of school-based writing-to-learn interventions on academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 29–58. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001029

De La Paz, S., & Graham, S. (2020). Strategy instruction in writing: Meta-analysis of effects for students with learning disabilities. Exceptional Children, 86(2), 111–129.

Graham, S., & Harris, K. R. (2018). Evidence-based writing practices: A meta-analysis of writing instruction for students in grades 1–12. Educational Psychology Review, 30(2), 445–476.

Graham, S., Harris, K. R., & Santangelo, T. (2024). Writing instruction and student achievement: A meta-analysis of writing interventions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 116(2), 215–234.

Graham, S., & Perin, D. (2007). Writing next: Effective strategies to improve writing of adolescents in middle and high schools. Alliance for Excellent Education. https://all4ed.org/reports-factsheets/writing-next-effective-strategies-to-improve-writing-of-adolescents-in-middle-and-high-schools/.

Graham, S., Harris, K. R., & Santangelo, T. (2024). Writing instruction and student achievement: A meta-analysis of writing interventions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 116(2), 215–234. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000701.

Lunsford, A. A., & Connors, R. J. (1995). The St. Martin’s Handbook (3rd ed.). St. Martin’s Press.

Shanahan, T. (2005). The National Reading Panel report: Practical advice for teachers. Learning Point Associates.

Shanahan, T. (2025). Leveled reading, leveled lives: How students’ reading achievement has been held back and what we can do about it. Harvard Education Press.