With 37% of fourth graders not reading at proficient levels (NCES, 2023), universal screening offers a powerful opportunity to identify and support students’ needs much earlier. These tools allow educators to assess foundational literacy skills—even before kindergarten—to provide insight into each child’s strengths and areas for growth. While medical screenings for standard growth milestones are widely accepted, early screening for learning disabilities like dyslexia still faces resistance (Anderson, 2023). Yet research shows that with timely, intensive intervention, up to 96% of students can meet grade-level reading expectations by the end of first grade (Torgesen, 2009). By integrating universal screening into school practices, educators can proactively tailor instruction and ensure all students have the appropriate support they need for academic success.

When and What to Catch

Screening can begin as early as age 3 (Puolakanaho et al., 2007), yet many schools conduct universal screenings upon entry to kindergarten and continue two to three times per year through first grade (Catts, 2021).

Common literacy areas assessed:

- Phonological awareness: recognizing and manipulating sounds in spoken language

- Letter and word recognition: identifying individual letters and words

- Phonemic awareness: hearing and working with individual sounds in words

- Rapid automatic naming (RAN): quickly naming familiar items like letters, numbers, or colors

- Language comprehension: understanding vocabulary, grammar, and spoken language

- Verbal working memory: temporarily hold and use spoken information in one’s mind

How Universal Screening Supports Students

Universal screening helps identify children at risk for dyslexia and other reading challenges. It serves as a valuable tool for monitoring progress, guiding interventions, and highlighting literacy strengths and needs throughout the school year. The data collected can inform the appropriate level of the multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) and evaluate whether current interventions are effective. Additionally, it can provide meaningful observations for families for a broader evaluation process.

Recognizing Signs of Dyslexia in the Classroom

Informed teachers may observe early indicators of dyslexia in their classrooms. These may include difficulties such as learning the alphabet, connecting letters to sounds, rhyming, and manipulating sounds through blending and segmenting. Students may struggle to read fluently and accurately, experience frustration with handwriting, or avoid reading altogether. Additional signs can include speech delays and a family history of learning challenges (Adlof & Hogan, 2018; Kearns et al., 2019).

Expanding the Role of Pediatricians in Early Literacy

Pediatricians play a vital role in a child’s development, yet their assessments rarely include early literacy skills. While standard developmental screeners cover areas like cognition, language, motor skills, and social-emotional growth, adding a focused evaluation of reading readiness could offer a more complete picture. This holistic approach would help families and educators better understand each child’s learning needs from the start of school and work together to better support them.

Why Early Intervention Matters

The earlier learners receive targeted instruction, particularly in foundational skills like phonemic awareness and phonics, the more likely they are to achieve grade-level proficiency and avoid long-term reading difficulties (Torgesen et al., 2001). Early intervention also helps reduce associated social-emotional challenges, such as frustration and shame. Moreover, dyslexia becomes increasingly difficult to remediate the later it is identified (Gaab, 2017). Universal screening does not need to be lengthy or expensive to produce valuable insights into each student’s literacy development and can provide timely data that helps educators deliver focused interventions.

Teacher Preparation Matters

As universal screening tools become more widely available, it’s essential that educators receive proper training on how to use them effectively. Teachers need support not only in administering these tools but also in interpreting the data and targeting specific lessons for class and individual student goals. Early screening, paired with targeted professional development, will strengthen our ability to identify and support students with dyslexia and other reading challenges.

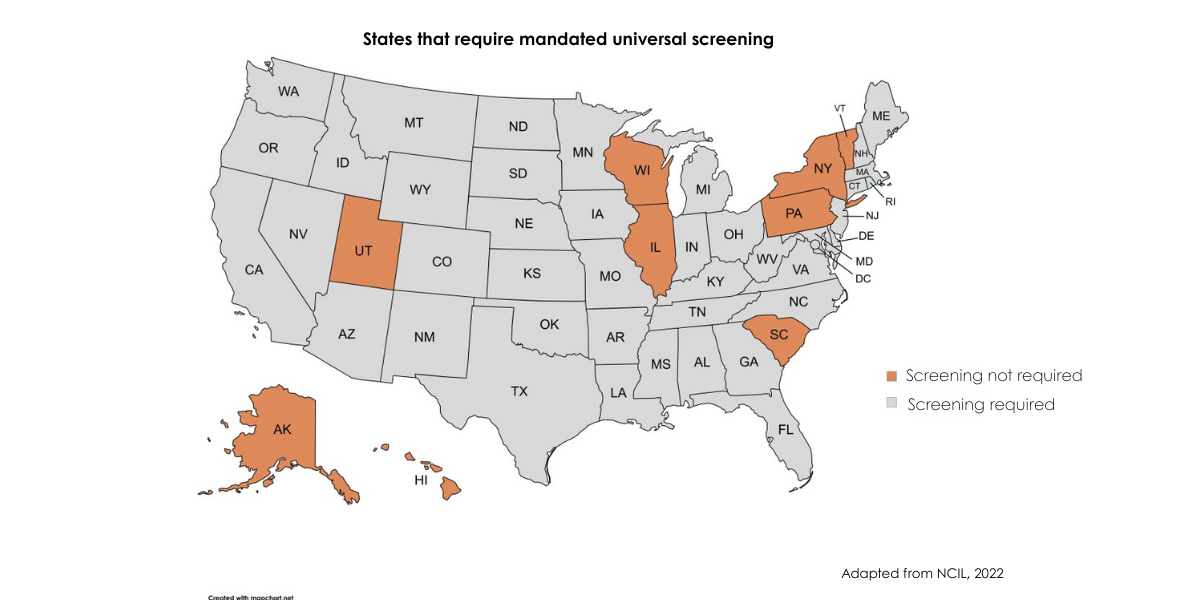

Universal screening is a powerful tool that ensures no student’s literacy needs go undetected. By embracing it alongside professional training and collaboration, it enables educators to more effectively meet the diverse needs of their students. Every state should pass legislation requiring universal screening—and your advocacy can drive that change. Contact your school district and state legislators to demand early literacy screening for all students. When educators and community members speak up, we can effect meaningful change, moving the needle on literacy outcomes.

References

Adlof, S.M., & Hogan, T.P. (2018). Understanding dyslexia in the context of developmental language disorders, Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49(4), 762-773, https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_LSHSS-DYSLC-18-0049

Catts, H.W., & Petscher, Y. (2022). A cumulative risk and resilience model of dyslexia. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 55(3), 171-184, https://doi.org//10.1177/00222194211037062

Colorado Department of Education. (2024). Colorado Dyslexia Handbook, 3.2.

Gaab, N. (Guest). (2023, October 19) The case for early dyslexia screening [Audio podcast]. Harvard Edcast. Retrieved from https://www.gse.harvard.edu/ideas/edcast/23/10/case-early-dyslexia-screening.

Gaab, N. (2017, February). It’s a myth that young children cannot be screened for dyslexia!, International Dyslexia Association, https://dyslexiaida.org/its-a-myth-that-young-children-cannot-be-screened-for-dyslexia/

Kearns, D.M., Hancock, R., Hoeft, F., Pugh, K.R., & Frost, S.J. (2019). The neurobiology of dyslexia, Teaching Exceptional Children, 51(3), 175-188, http://doi.org/10.1177/0040059918820051

National Center for Education Statistics. (2023). Reading Performance. Condition of Education. U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cnb

Puolakanaho, A., Ahonen, T., Aro, M., Eklund, K., Leppanen, P.H.T., Poikkeus, A.M., Tolvanen, A., Torppa, M., & Lyytinen, H. (2007). Very early phonological and language skills: Estimating individual risk of reading disability, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 48(9), 923-931, http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01763.x

Torgesen, J.K. (2009). The response to intervention instructional model: Some outcomes from a large-scale implementation in reading first schools, Child Development Perspectives, 3(1), 38-40, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2009.00073.x

Torgesen, J.K., Alexander, A.W., Wagner, R.K., Rashotte, C.A., Voeller, K.K., & Conway, T. (2001). Intensive remedial instruction for children with severe reading disabilities: Immediate and long-term outcomes from two instructional approaches, Journal of Learning Disabilities, 34(1), 33-58, https://doi.org/10.1177/002221940103400104