Graphic organizers are widely recognized in educational research as effective tools for improving comprehension, critical thinking, and memory retention (Graham et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2004; NRP, 2000). One key area they support is vocabulary depth, or the richness and complexity of word knowledge, which includes understanding relationships among words within semantic networks (Hadley et al., 2018). These networks are flexible and grow as students learn new words, especially when vocabulary is introduced in meaningful, context-rich ways that connect to prior knowledge (Borovsky et al., 2012).

To foster this growth, instruction should offer frequent, purposeful opportunities for students to explore word relationships. Visual organizers can play an important role by making these relationships explicit (Hiebert, 2020; Kim et al., 2004). For example, semantic maps highlight associations among words and their meanings, while concept maps show how ideas relate to one another conceptually. Both help make abstract concepts more accessible and concrete.

Semantic Maps

Semantic maps for vocabulary instruction are designed to develop word knowledge by visually displaying the associations and meanings connected to a particular term. They help students connect new information to their prior knowledge, which supports schema development and deeper understanding (Heimlich & Pittelman, 1986).

A focus word and/or concept is centrally placed, with related words radiating outward. These surrounding terms might include synonyms, antonyms, attributes, functions, or other connected ideas. When students organize vocabulary this way, they are not only learning new words, but they are also learning how those words connect with what they already know. This supports both comprehension and recall (Stahl & Nagy, 2006).

Semantic maps can be used before, during, or after reading. Before reading, maps activate students’ background knowledge and prime their mental lexicons. During or after reading, semantic maps can be expanded or revisited to reinforce relationships among words and extend meaning across contexts. These tools help students organize, remember, and highlight important information as they are learning (Heimlich & Pittelman, 1986).

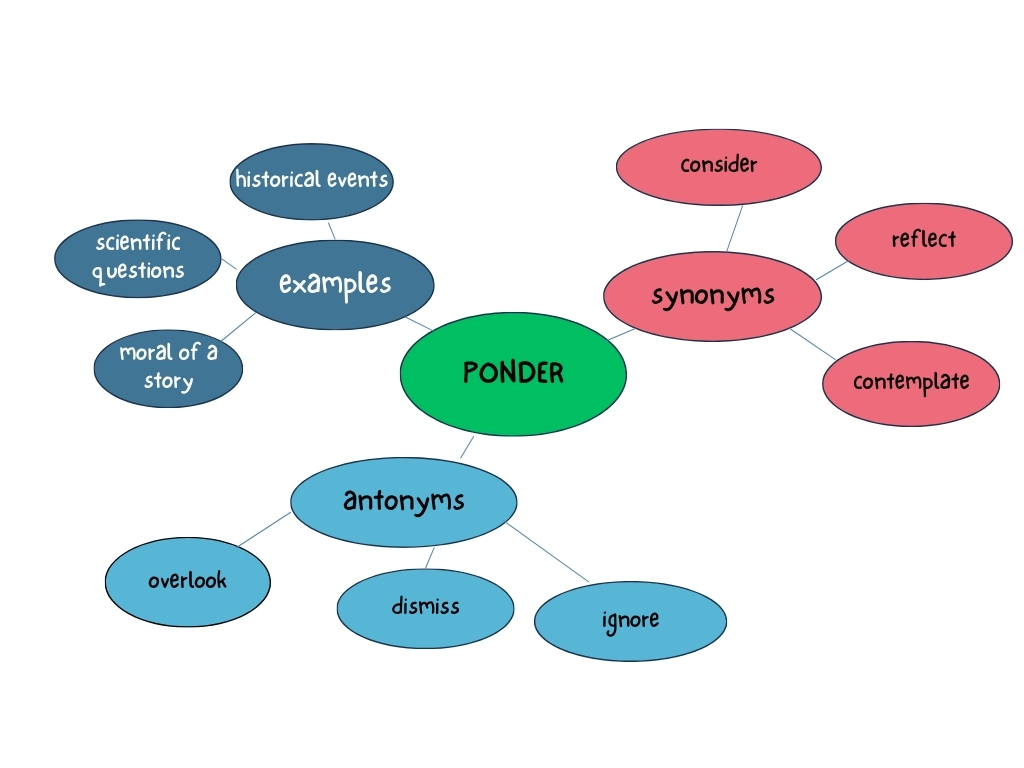

Semantic Map: Ponder

In this semantic map activity, the focus word is ponder: to think carefully about something. Students deepen their understanding by generating synonyms such as reflect and contemplate, and antonyms like dismiss and ignore. To encourage application, teachers may ask, “What have you pondered in one of your classes recently?” They can then follow up with prompts for elaboration. This approach helps students articulate their reasoning, build connections, and engage with vocabulary in meaningful, academic contexts.

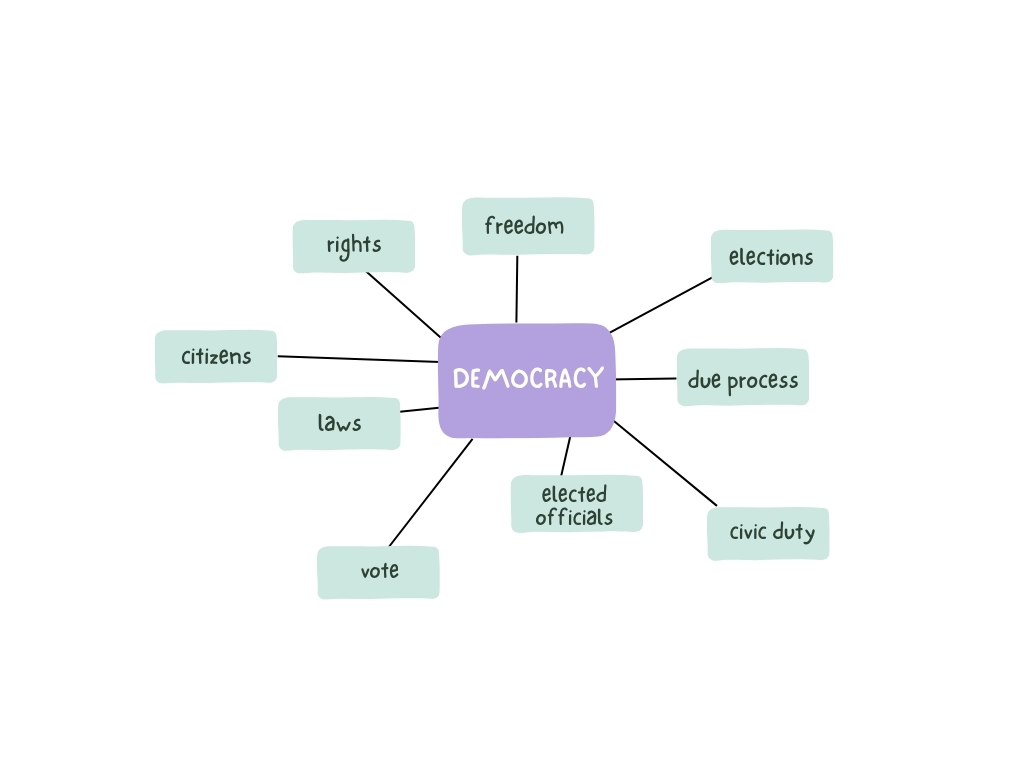

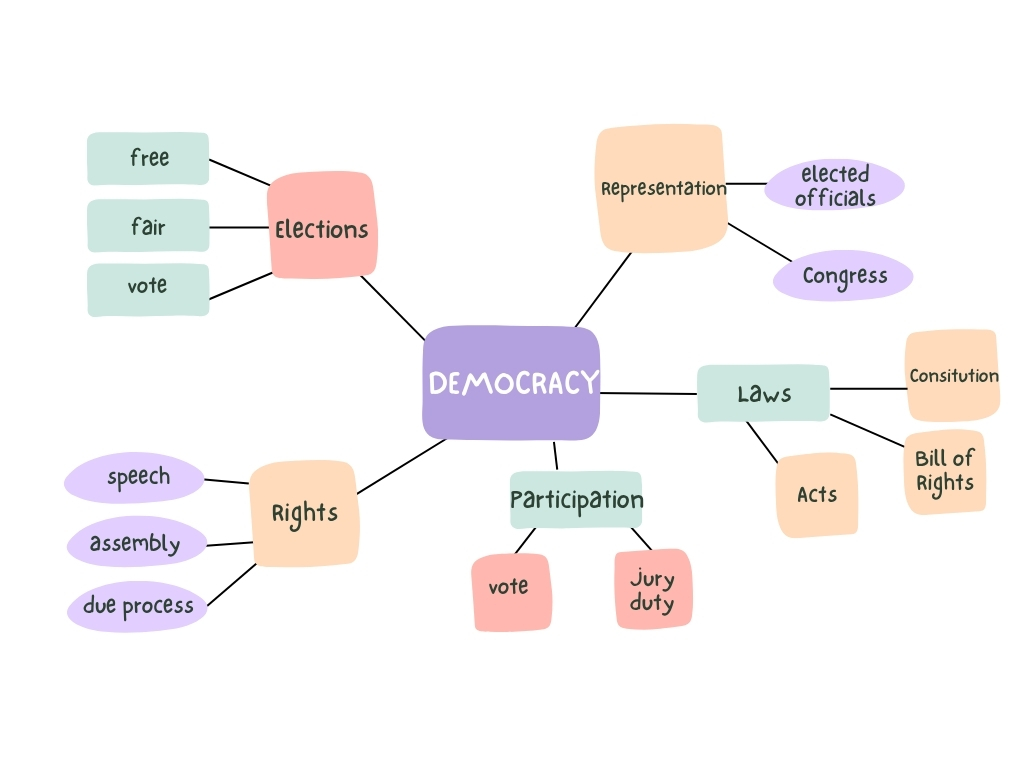

Semantic Map: Democracy

Using semantic maps to teach discipline-specific terms can be especially valuable. When students map words within a content area, they deepen their understanding of those terms in context, which strengthens conceptual understanding and promotes long-term retention (Bravo & Cervetti, 2008; Fitzgerald et al., 2021).

Consider two examples using the word democracy. In the first, the teacher may ask, “What words are related to democracy?” Students then brainstorm associated terms such as freedom, elections, laws, citizens, vote, due process, and elected officials. These responses are recorded around the central term: democracy. This activity helps learners activate and build an initial semantic network that lays the foundation for deeper word understanding and more structured concept development.

In the second example, the teacher begins by asking a deeper, guiding question: “What are some of the features of a democracy?” As students begin to offer words like vote, freedom of speech, or Constitution, the teacher uses follow-up questions to guide and structure their thinking, rather than immediately listing the responses on the board.

This instructional move shifts the activity from brainstorming to concept building. The teacher prompts students to consider whether their ideas represent broad categories or if they belong within one. For example, when a student says “freedom of speech,” the teacher might respond, “Yes, freedom of speech is an important right in a democracy. Let’s write rights as a category, and then we’ll connect speech to it.”

From there, the teacher may ask, “What are some other rights people have in a democracy?” This prompts students to generate related terms like assembly or due process. As the process continues and students offer more ideas, terms are organized within a semantic structure. Through this approach, students learn how words are related, reinforcing both vocabulary depth and disciplinary knowledge.

Concept Maps

Concepts maps are another type of graphic organizer that can be used to highlight key terms and ideas. While similar to semantic maps in that they help students visualize connected terms, concept maps organize information in a more intentional manner to emphasize how words and concepts relate within a broader structure of knowledge.

A concept map typically begins with a central idea or overarching concept placed at the top or other strategic location on the map. From there, the map branches out into related sub-concepts. Linking words or phrases may be included to clarify relationships. This structure enables students to organize knowledge in ways that highlight the logical and functional relationships among words and concepts (Stahl & Nagy, 2006; Manoli & Papadopoulou, 2012; Vaughn et al., 2024).

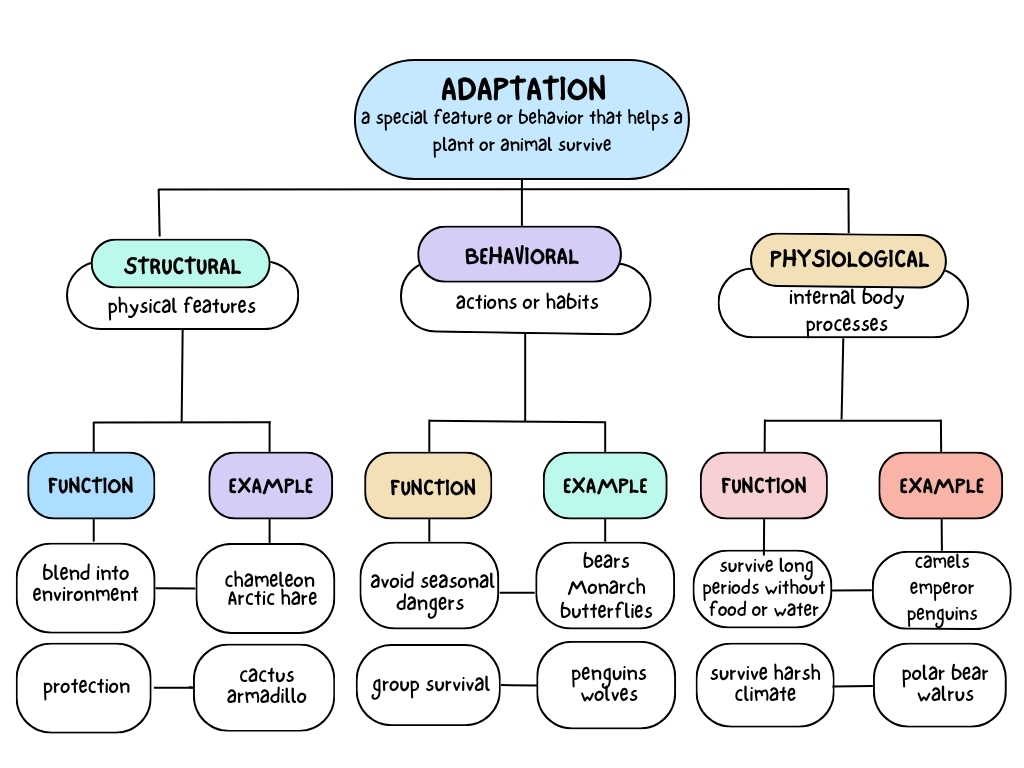

Concept Map: Adaptation

In this concept map activity, the teacher begins with a guiding question: “What types of adaptations have we learned about?” As students respond with ideas such as “habits” or “body features,” the teacher can steer the discussion toward the vocabulary subcategories: structural, behavioral, and physiological adaptations. The teacher would then prompt students to identify the function or purpose of each type, along with examples. For instance, if a student offers the term camouflage, the teacher might respond, “Great! Camouflage is a physical feature that helps animals blend into their environment. Let’s place that under structural adaptations.” The teacher then asks, “What are other physical features that help organisms survive?” The teacher may encourage students to generate related terms, such as fur thickness, body shape, or leaf structure. As more ideas emerge, the teacher helps students sort them into the correct sub-categories.

Concept maps provide a structured framework to visualize relationships between words and ideas, especially in content- rich subjects like science and social studies. This visual could further serve as a structure to support comprehension, leading to a structured writing activity.

Graphic organizers can be adjusted across subjects and grade levels, making them highly versatile. Teachers should explicitly model the use of graphic organizers through direct instruction. Once students demonstrate understanding, educators can guide them—through gradual release—toward applying these tools collaboratively with peers. Throughout a unit, graphic organizers can be revisited and expanded to deepen comprehension and reinforce key concepts. By incorporating semantic and concept maps, educators make conceptual connections visible and promote long term retention. When used consistently, graphic organizers help learners develop metacognitive strategies that improve their ability to organize, analyze, and apply new knowledge across content areas.

References

Borovsky, A., Elman, J. L., & Kutas, M. (2012). Once is enough: N400 indexes semantic integration of novel word meanings from a single exposure in context. Language Learning and Development, 8(3), 278–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/15475441.2011.614893

Bravo, M.A., & Cervetti, G.N. (2008). Teaching vocabulary through text and experience. In A.E. Farstup & S.J. Samuels (Eds.), What research has to say about vocabulary instruction (pp. 130-149). International Reading Association.

Fitzgerald, J., Elmore, J., & Relyea, J.E. (2021). Academic vocabulary networks matter for students’ disciplinary learning. Read Teach, 74(5), 569-579. http://doi:org/10.1002/trtr.1976.

Graham, S., Bruch, J., Fitzgerald, J., Friedrich, L., Furgeson, J., Greene, K., Kim, J., Lyskawa, J., Olson, C.B., & Smither Wulsin, C. (2016). Teaching secondary students to write effectively (NCEE 2017-4002). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE), Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved from the NCEE website: https://whatworks.ed.gov.

Heimlich, J.E., & Pittelman, S.D. (1986). Semantic mapping: Classroom applications. International Reading Association.

Hiebert, E.H. (2020). The Core Vocabulary: The Foundation of Proficient Comprehension. The Reading Teacher, 73(6), 757–768. https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1894.

Kim, A. H., Vaughn, S., Wanzek, J., & Shangjin Wei. (2004). Graphic Organizers and Their Effects on the Reading Comprehension of Students with LD: A Synthesis of Research: A Synthesis of Research. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 37(2), 105-118. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222194040370020201

Manoli, P., & Papadopoulou, M. (2012). Graphic organizers as a reading strategy: Research findings and issues, Creative Education, 3(3), 348-356, https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2012.33055.

National Reading Panel. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the subgroups. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Stahl, S. A., & Nagy, W. E. (2006). Teaching word meanings. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Vaughn, S., Boardman, A., & Klingner, J. K. (2024). Teaching reading comprehension to students with learning difficulties. Guilford Publications.